Alex Janvier and the eternal struggle

By Tim McCauley |

His earliest works, at age 15, were religious commissions by the school; "Our Lady of the Tepee" (1950) is an ideal example of the inculturation of the Gospel, as Janvier portrays Mary with native features and includes Indigenous iconography such as a tepee. As Janvier developed his skill, he leaned toward abstract art, but many of his pieces are much more engaging and accessible in comparison with other artists encased in an unrelenting monotony of style. (Even those unfamiliar with art can instantly recognize a painting by Jackson Pollock, with his non-technique of pouring and flinging his paint on the canvas, or a work by Piet Mondrian with his weary discipline of geometric shapes and straight lines). Janvier's work can be delightful in its diversity.

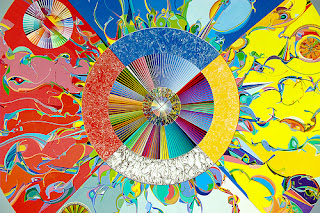

The beginning of the exhibit presents us with a series of mandala-circle works with a sparing use of calligraphy-style wisps of paint. But then his style evolves continually. One of Janvier's early abstract works, "Eternal Struggle," (1966) conveys the sense of a profusion of life in a dense jungle, with orange, blues, greens and whites in semi-floral patterns, twisting and converging in a vortex. All human beings struggle to express our souls in the external world, through art, work, and relationships. Someone once described the soul as a diamond. But it can also be a furnace of passionate and conflicting emotions, an explosion of colours of inchoate beauty that cries out for meaning and form. However, abstract artists tend to be suspicious of any external imposition of meaning. They prefer to explore colours without obvious form and "pure" emotion without intrusion from the intellect.

"Fly, fly, fly" (1981, oil on linen) is a prime example of the potential of such art to elicit feeling. The indistinct image reminds one of a praying mantis or other stick insect, twisted and splattered on the surface of the linen. The word "chthonic" comes to mind, as if we were seeing an alien creature raised from the underworld, a fascinating but disturbing image. Of course artists can help us explore our unconscious. But to which image are they drawing our gaze -- to a monster lurking in a cave, or the image of God reflected in a diamond?

My second time at the exhibit I met a German art student who compared Janvier favourably to German expressionists, while also remarking on Janvier's unique style. He combines cheerful colours with dark themes. The expressionists normally shun soft colours such as light blue and pink, which Janvier freely employs. In 1989, Janvier explored memories of his residential school experience in 33 paintings, some of which are included in the exhibit. There are faceless children in stiff uniforms, suggesting an imposed conformity, yet all is rendered in bright colours! It evokes a sense of the irrepressible energy of the human soul.

In the context of the current cultural narrative of all residential schools being an unquestionable evil of relentless oppression, it is interesting to note, as the writers of the exhibit inform us, that the first school that Janvier attended encouraged him to explore his talent. The place of his "oppression" taught him to express himself. One wonders if, without those teachers at the residential school who recognized and encouraged his artistic gift, would there be an exhibit today? This might indicate the need for a more honest appraisal of the legacy of residential schools, recognizing the mix of good and evil in all human institutions and in every human being.

Near the end of the exhibit, almost as an afterthought, is a casual drawing of a priest entitled "Old Rev." The commentary of the creators of the exhibit is most instructive. We are informed that "Old Rev" was "instrumental in suppressing Dene culture through his teaching of Christianity which was presented as superior to their beliefs." First, let us make a clear distinction between people and truth. The European Christians who came to Canada were in no way superior, as human beings, to the native people. We are all sons and daughters of the one God. Furthermore, as John Paul II remarked, on his visit to the Martyrs' Shrine in 1984, "Jesus Christ, in the members of His Body, is Himself native." At the same time, the truth of God that Christ came to reveal -- that the Divinity is not an arbitrary power or a jealous demiurge, but a loving Father who created everything out of nothing, and desires only our good and our happiness -- this teaching is eminently superior to the half-truths of many pagan myths, whether they be Greek, Roman or Norse, Huron, Ojibwe, or Dene.

It is right for us to be outraged by religious hypocrisy. For anyone -- whether priest or nun, parent or teacher -- to tell children stories of Jesus but treat them with a sense of superiority, indifference, anger or cruelty -- such people bear the weight of serious scandal. From my own experience growing up in the Anglican Church, I can testify to the scars that such treatment leaves in the souls of children, and our collective need for healing. But it is wrong for us to blame God for the suffering in our lives, and a tragic conclusion for our own souls and our own happiness if we allow the weakness or malice of human beings to prevent us from coming to know Christ and the truth He reveals.

The current secular spin on the missionary efforts of Christians toward Indigenous Canadians would like to airbrush out of history personalities like Joseph Chihwatenhwa, a Huron native of the 17th century. When he met the Jesuit missionaries, he found that the truth of God they proclaimed corresponded with his own personal spiritual quest. By a supernatural instinct, he had already been withdrawing his spirit from some of the pagan practices into which he had been born. For instance, he and his wife had been married only once, and refused to indulge in the not uncommon practice among the Hurons of spouse sharing. They avoided feasts imbued with pagan ritual, and to the genuine astonishment of the Jesuits, neither he nor his wife smoked tobacco! When the missionaries told him about Christ, the truth resonated with something deep in his spirit, and he was drawn to belief as a fulfillment of his own deepest desires. (It is worth noting that after Joseph was murdered in secret by Iroquois raiders, many of the Jesuit priests regarded him as a saint in heaven, and there is a movement today for his canonization).

There is still so much potential in a fruitful dialogue between European Christian culture and native Canadian traditions, to enrich all Canadians. A true Christian ethos will always have a deep respect for nature as a gift and revelation of the Father-Creator. But secular European/Canadian culture can manifest a brutal, instrumental, capitalist and exploitative view of nature. Indigenous Canadians, for one, can help us all offset this danger. They have dwelt in this land for centuries, almost as if their flesh was formed from the clay of this particular Canadian earth. One of Janvier's painting, Nehobetthe (Land Before They Arrived, 1992), captures the magnificent natural diversity of Canada, with images of deer, bison, moose, rabbits, beavers, and eagles. Indigenous people can help us root ourselves more deeply in the land in which we dwell, living in our bodies grounded in the earth, rather in the virtual reality of our minds, detached from the smells and sounds of the world around us, cut off from other people and our own selves.

My hope and prayer for Janvier and others like him is that they will continue to explore the "colours" of their soul, their own inner emotions, in our common "eternal struggle" both to express ourselves and discover God. Form does not oppress colour, but fulfills it. The Christian message does not oppress the human person, but liberates him. God is for us, not against us. He is on the side of human beings of whatever ethnic background, for we are all His beloved children. Christ Himself gives us the tools to express ourselves in the art of life, and by His death and Resurrection, frees us from all forms of slavery and oppression, restoring our dignity and joy as beloved sons and daughters of our common Father.

Photo Attribution: Morning Star (Detail), Alex Janvier, 1993, file AlexJanvier MorningStar.jpg, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 License